by Stefan de Baar

The Vrijheidsmuseum, located in Groesbeek, has taken steps to tell the stories of how the war impacted ‘love’ during the Second World War whilst the Netherlands was occupied by Nazi Germany. Through this they shine a light on the lives and history of regular everyday people. We have taken the opportunity to visit their exposition ‘Liefde in de Oorlogstijd’ or ‘Love in Wartime’ to see for ourselves. The war refers to the Second World War.

In this exhibition visitors can truly explore how loving relationships of all kinds were affected by the war. For some the outlawing of dancing might just be the plot for Herbert Ross’ 1984 film Footloose. But during the Nazi occupation in the Netherlands it was reality. Dancing, which at the time was seen as an important display of public intimacy, was actually outlawed in some Dutch regions such as the city of Groningen. This however was not the only place dancing was banned during the occupation. It was prohibited in many cities and towns across the Netherlands. This may seem odd but there have been prior instances in history where the arts have been put to a stop as a symbolic gesture in times of war or political upheaval. For example, according to some accounts, Alexander the Great outlawed flutes and other kinds of music to mourn the death of his “closest friend” Hepheastion (Plutarch 72.3).

The subject matter presented within this exhibition is broad, capturing a spectrum of relationships over this time. The different experiences of Dutch women who dated soldiers were shaped by which force they represented. The love between Dutch women and allied-troops who were perceived as heroes and liberators were celebrated and women followed their newly found lovers across the pond to the United States or Canada, leaving everything and everyone they knew behind to chase love. But those women who found love with the occupying forces, or those who became single mothers experienced significant stigma over the 40’s and 50s. For example, those Dutch women who had relationships with Nazi troops were hunted on so-called “moffenmeiden” after the Netherlands was liberated from Nazi occupation.. These girls and women who had fraternized with the occupiers often had their heads shaved forcefully, and were smeared and mocked publicly in cruel displays of violence.

The exhibition gives a podium for the realities of war and the sexual violence which is often used by the occupying force. Instances of this occurred on both the East- and the West-front. The exhibition is created with care which clearly shows how the museum tackles these sensitive subjects. Items representing the stories of survivors are veiled behind a curtain accompanied by a sign which warns visitors who might want to avoid certain topics. This also makes the exhibition appropriate for all ages, despite the vintage vibrators hidden Behind one of these curtains from before the war. These relics provide a contrast to today’s rose shaped, wireless and convenient devices, showing how access to pleasure has evolved over time.

Whilst visiting this exhibit, one will run into a pair of pants hung against the wall. A strange sight at first but it is however a beacon of love and resistance against the occupational forces. This pair of panties was made by Anton van Woezink, who worked as a clothier and according to the story he was forced to make uniforms for German soldiers. In secret, he used bags of sugar and a piece of cloth to make these underpants,which he had to smuggle out of the workshop by wearing them himself. On the fourth of February 1943, he gifted it to his wife as a wedding present.

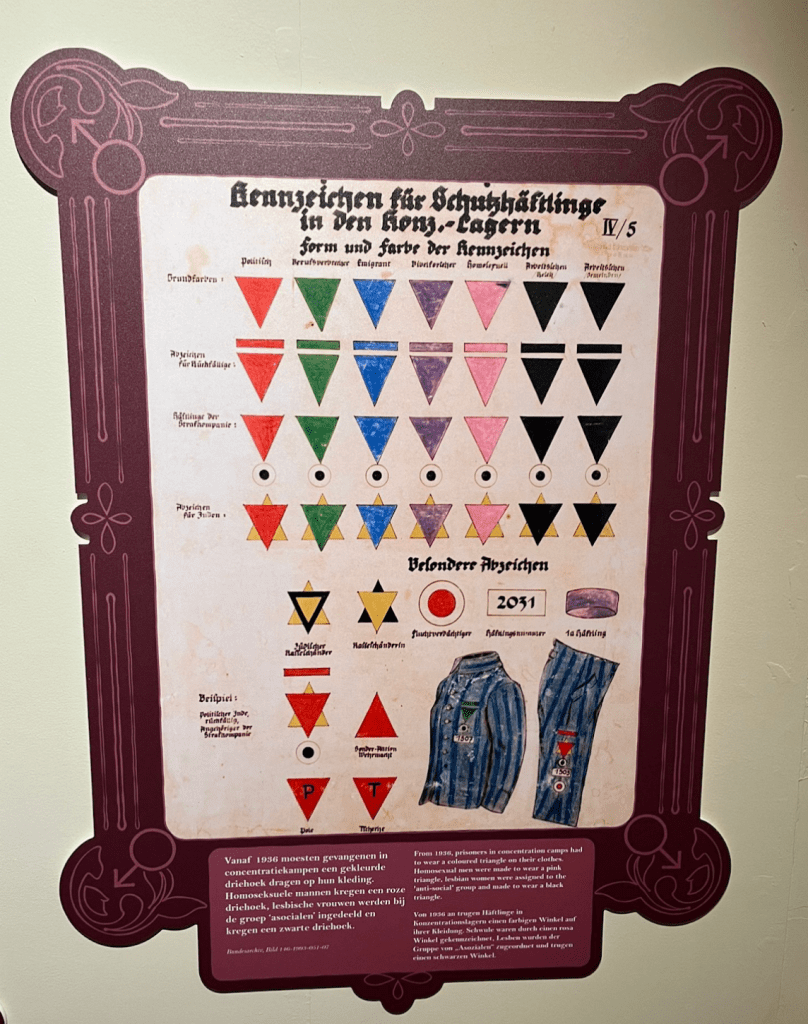

The Freedom Museum also takes this opportunity to highlight LGBTQI+ relationships during World War Two. Queer people have always existed and this showcases how their relationships were also affected during the war. German LGBTQI+ were one of the minority groups who were targeted by Nazi soldiers and who were shipped to and terminated in concentration camps. Many will be familiar with the Star of David that Jewish people were forced to wear that enabled public discrimination and surveillance all throughout the Nazi occupied Europe. Queer people were branded with a pink triangle to showcase their queerness to others. As the image below demonstrates, all people who were sent to concentration camps were branded based on their identity. The pink triangle has since been rebranded as a positive symbol for self-identity within LGBTQI+ communities.

One of the most touching items for display is a letter written by American soldier, Brian Keith, titled ‘Letter to a G.I.’ in which Keith writes to his former lover, ‘Dave’, with whom he had planned to reconnect after they had returned home from the war. Dave however, never returned to his home across the Atlantic Ocean. Within this letter, Keith opens his heart and reminisces on their time together and the plans they had made together. But to read the full letter and to appreciate more stories of love during war, the exhibition can be visited at the Vrijheidsmuseum in Groesbeek and is open until the 6th of April. More information on their other exhibitions or opening hours can be found on their website: https://freedommuseum.com