by Trine Linke

In her 2023 experimental documentary film Between Delicate and Violent writer and director Şirin Bahar Demirel investigates how memories are made and documented, and how to navigate memories which were concealed or hidden. Probing her own family’s memories from photo albums, videos, paintings and stitchwork for the traces of hands, she constructs a new history of memories which were shameful and kept hidden. The memories which “pretended to have never existed” are those of her grandmother’s domestic abuse and mental illness. With her guiding question, “How many ways to step through the memories?” Demirel takes the viewer on a multimedia journey through these material archives, in search for multiple modes of understanding a fractured and complex history. Demirel leaves her own traces on the material subjects of her analysis – touching them, painting over them and animating the frames, collaging them, juxtaposing and superimposing them, and even destroying them with a scalpel. Through this second visual narrative, she also questions the validity of the profilmic story the family photographs present to onlookers. The profilmic describes the objects and visual data captured by a camera, whereas the afilmic is everything that exists independently from these captured images; such as objects and actors outside of the scope of the camera, and also their possible context and relation to the objects infront of the camera (Kessler 192). Frank Kessler describes that, because the “afilmic remains irreducible to such a recording”, the profilmic can be considered an interpretation or discourse of the intangible afilmic – this also means, that the afilmic and profilmic do not have to follow the same narrative. (Kessler 192) Between Delicate and Violent’s strong visual language and essayistic approach to an imagined narrative seem to defy clear assortment to a singular mode of Bill Nichols’ categories for documentary. Nichols’ categories act as subgenres for documentary films, which come with certain conventions, such as styles of narration and narrative. This essay seeks to answer the question: How does the use of animation to visualise the invisible and afilmic influence the categorisation of Between Delicate and Violent in Nichol’s modes?

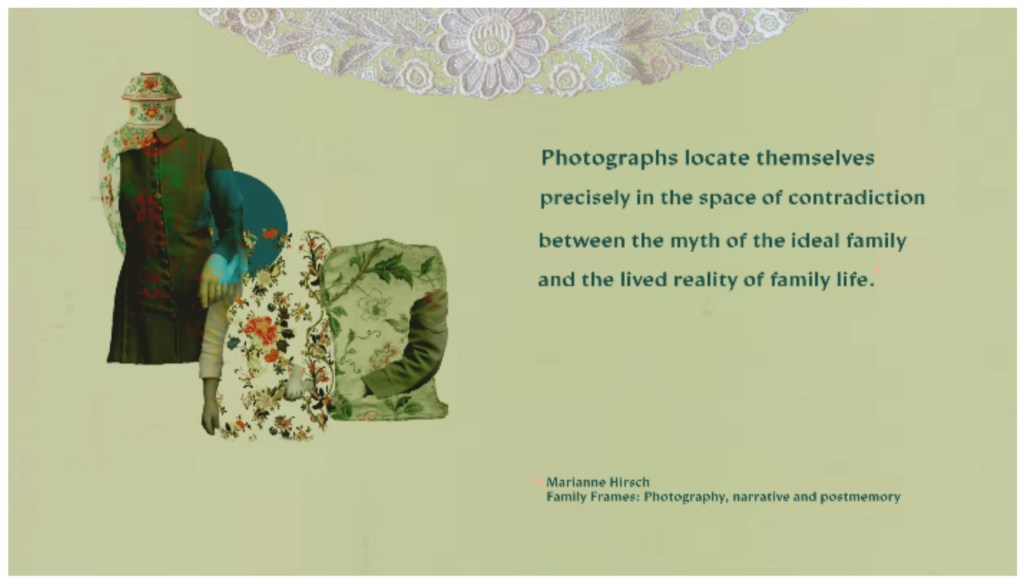

In Introduction to Documentary, Nichols explains that documentaries are a proposed view of the world, using indexical images and shots and providing an interpretation of them (Nichols 24). Often, as visual support or evidence, photographs are used to sustain these interpretations. Analogue photography carries a privileged status as a document, due to its iconic and indexical qualities: the object’s presence on the photograph resembles reality, and is also needed for the chemical process of the photo itself (Ehrlich 56). Further, photography acts as an extension and “an artificial eye” for the beholder, making a moment accessible to a viewer permanently (Koepnick 98). However, this idea of truthfulness is complicated by the notions of afilmic and profilmic presence. In his essay “What You Get Is What You See: Digital Images and the Claim on the Real” Frank Kessler explains that the indexical power of photography is only limited to the profilmic; the physical objects in front of the camera (192). Photography, without additional narrative and information, cannot give the full context of a scene. The afilmic, which is the uncaptured and independently existing reality, remains up to the interpretation and speculation of the observer. Şirin Bahar Demirel transfers this trait onto the staged nature of family photographs and memories. If we lack access to the afilmic and can only speculate it, what do we really know about the validity of the presented reality of a photograph? What is perhaps impossible to show due to its non-physical nature? We can never truly grasp the situation in which a photo or video was captured – something which is increasingly difficult with the speed at which AI-generative images evolve to mimic true captures of life. However, Demirel’s editing of her own footage represents an important practice of giving voices to those who are historically robbed of it; even if this is equally as staged as she assumes her family photos to be.

A traumatic experience, such as domestic violence, “shatters the fabrics of narrative, memory, and historical experience” (Koepnick 106). The complex psychological damage is materially invisible to us, but Demirel proposes that it influences us physically across generations.

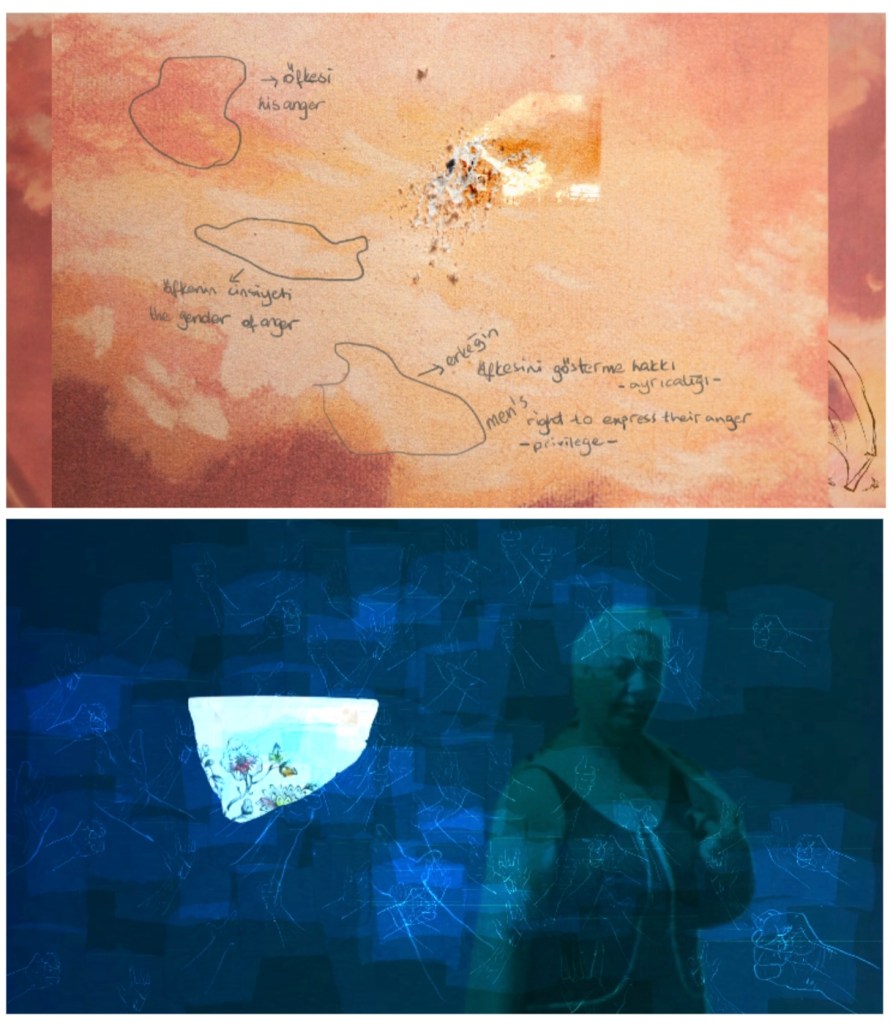

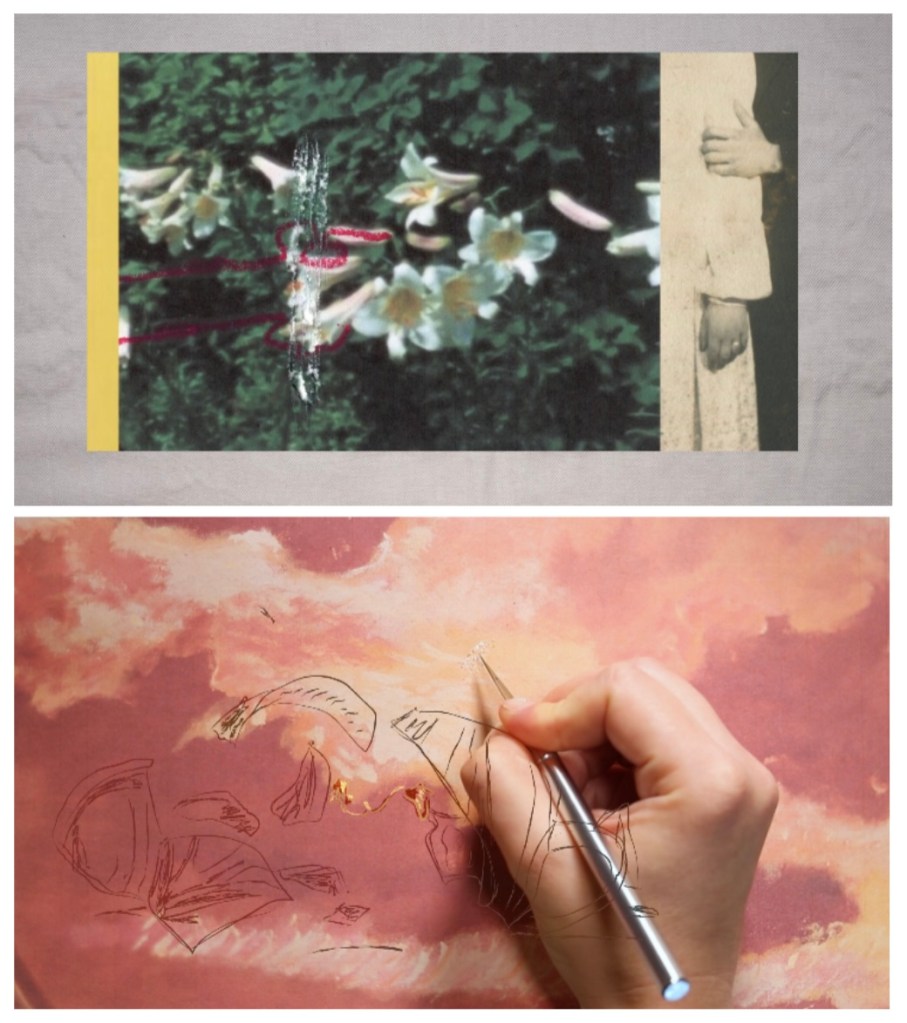

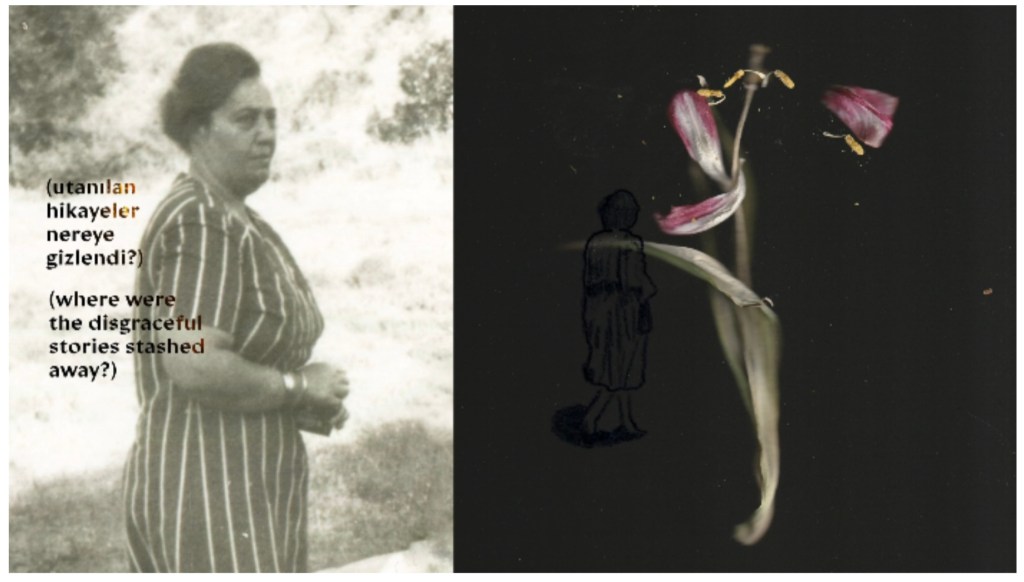

Between Delicate and Violent tackles the issue of portraying the afilmic and unrepresentable consequences of domestic violences through Demirel’s interaction with the documents she analyses. Where her grandfather’s hands hide violence in his paintings (fig. 1), she circles it for the viewer, painting his hands and ascribing them emotions. Where language fails to grasp the complexity of traumatic memories, Demirel opts to let the visuals and sounds speak for themselves: overlapping stills of threatening hands over the sounds of shattering china (fig. 2), a colour transferred from a hand onto a flower next to her grandfather’s hand gripping his wife’s arm (fig. 3). Demirel parallels the staged nature of family photographs with her own manipulation, the violence of domestic abuse with the destruction of a painting (fig. 4). Within the documentary, the conventional photographs are just as real as the projections of her ideas of grandfather; both seek to understand the material in front of them and both can never grasp the afilmic possibilities of the past. However, Demirel’s projections aim to give voice to those whose voices and realities are purposefully hidden. Since there is no material evidence to the reality she proposes, she creates and materialises the evidence of her grandmother’s trauma with her own animations. Nea Ehrlich credits the possibility of simulating “factual data that are not otherwise available” due to their intangible nature to animation’s ability to “visualise complex ideas, structures, and systems” (71, 69). Ehrlich further explains that animations have been “widely used in documentaries in order to portray subjective accounts of events” (74). In Between Delicate and Violent Demirel’s relation to her grandmother’s suppressed and shamed memories is another of these simulated realities. Through animation, she can portray not only her grandmother’s figures, but also abstract concepts such as memories flowing from hands onto flowers, onto stitch work, or metaphorically compare the effects of domestic violence to the destruction of the fabric of a painted canvas (fig. 4).

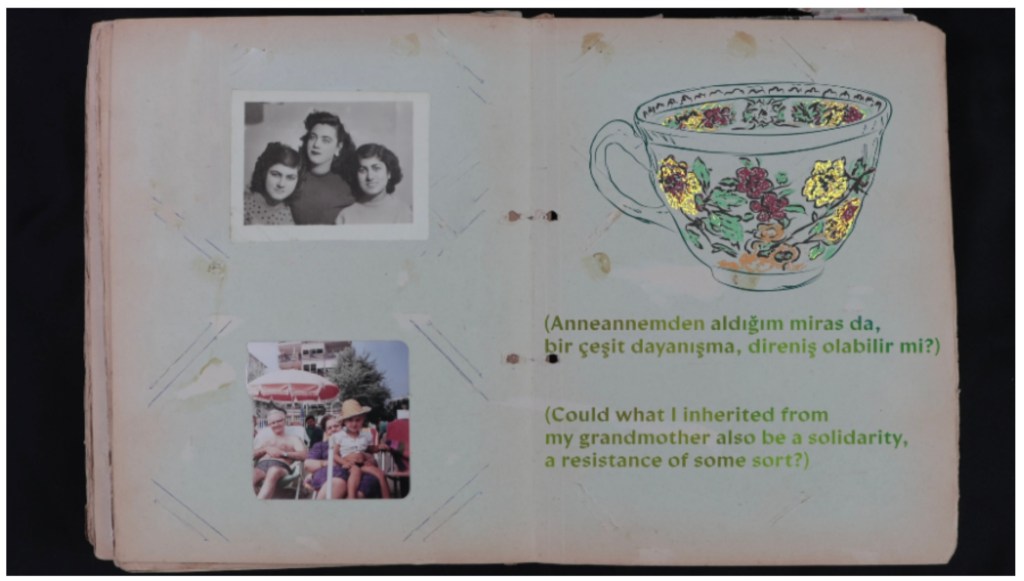

In this way, Demirel acknowledges the multiplicity of interpretations of the afilmic of her family photographs and the power of narration to “correct the deceptive surface of the photographic image” (Koepnick 104, 102), while also clearly indicating her reading and narrative to the audience. The “blatant constructedness” of animation acts as a mirror to the rhetoric point Demirel makes about the truth claim of photos (fig. 5), suggesting that these photos construct a family image which enforces a hierarchy of memories, in which some are considered shameful and need to be hidden away (Ehrlich 56-7). Through this format, which heavily emphasises the arguments Demirel makes through visuals alone, the rhetoric and visual narrative are interconnected and inseparable. At points, some of Demirel’s questions are only answered by images (fig. 6).

Because of this reliance on visual association, Demirel’s documentary bears characteristics of the poetic documentary. Nichols describes poetic documentaries as gleaning historical material and transforming it “in distinctive ways”, creating mood and tone through editing and music, something Demirel does through her artistic interaction (17, 116). The main messaging of the poetic mode is transferred not through rhetoric argument, but “associations and patterns that involve temporal rhythms and spatial juxtapositions” (Nichols 116). While associations and juxtapositions are a big part of Demirel’s non-rhetoric argumentation and at times essential, she still also relies on her own narration. In that way, Between Delicate and Violent more closely resembles the performative mode and essay film. In the performative mode, the filmmaker’s voice acts as a tool of organisation, and the expressive qualities of sound, music, and imagery are used to support the rhetoric narrative (Nichols 109). Because of the subjective and expressive qualities of this mode, it is often utilised as a channel by marginal and frequently misrepresented voices, to represent oneself authentically in a corrective manner (Nichols 152-3). This ability follows from the bottom-up approach to retelling history, as it feels to one specific person and group, instead of the conventional top down approach found in the expository mode (Nichols 153). In other words, performative documentaries tend to highlight the experiences of often marginalised individuals to explain a moment in history, instead of following the conventional approach of history books, which explain history on a larger and broader scope. The emphasis on complex and situated knowledge used in performative documentaries also intertwines with the close relationship between the filmmaker and their subject; such as Demirel’s with her grandmother and their inherited trauma (Nichols 111).

This personal aspect makes performative documentaries inherently self-reflexive and subjective, a quality they share with essay films (Munteán). The essay film further invites the viewer to think along with the filmmaker – something Demirel achieves through her rhetoric questions answered only by images, which are open to the viewer’s interpretation. Most of this thinking-along happens in the form of analysis and interrogation of the documents Demirel presents to us; she unites both the testimony and investigation in the documentary. Through her investigation of the material, she constructs a testimony of memories and memory transferral which speak for the experience of women like her grandmother, whose stories were purposefully hidden. The quality of investigations to offer a new perspective by analysing gathered evidence allows her grandmother to speak and recount her experience through her material legacies, giving proof to the domestic violence she experienced. Her testimony “creates a sense of a person or a groups experience through the words of those who lived through it” (Nichols 154). The embodied and nonverbal quality of her testimony reflects the nature of the subject matter – trauma – which escapes conventional narration. At the same time, the film’s investigation is also about Demirel’s search for navigating these memories, and her own relationship to them. At the end of her essay film, she poses the question if there is a way to reconfigure the inherited trauma as resistance (fig. 7). This open end, a call to reconsider how we deal with memories of inherited trauma, allows the viewer to reflect on their own stories that may be written.

In conclusion, Between Delicate and Violent is an essay film with performative and poetic elements. The filmmaker delivers a self-reflective and personal narrative navigating her grandmother’s trauma through both linguistic, tactile and visual means, which at times play supporting and independent roles to each other. To construct her arguments, Demirel employs investigative tactics on the material evidence of family photographs, paintings and fabric art, dissecting the traces of hands and letting them speak in testimony through means of multimedia animation and visual metaphor. The medium of animation parallels the constructed nature of photographs, highlighting the limiting perspective of the profilmic and offering an afilmic perspective she experienced to be silenced. These testimonies are experienced through hands, and their material traces, with Demirel’s traces and voice guiding the viewer alongside her search. Because of the subject matter of the proposed afilmic, the poetic visual language of animation acts as a more interpretive and malleable substitute to where words fail. In this way, Demirel weaves the visual and associative qualities of the poetic mode with the more rhetoric and representative performative mode.

References:

Between Delicate and Violent. Directed and written by Şirin Bahar Demirel, EYE Experimental, 2023. Vimeo.

Demirel, Şirin Bahar. “Between Delicate and Violent.” Şirin Bahar Demirel, 24 Oct. 2024, sirinbahardemirel.com/between-delicate-and-violent.

Ehrlich, Nea. “Defining Animation and Animated Documents in Contemporary Mixed Realities.” Animating Truth: Documentary and Visual Culture in the 21st Century, Edinburgh University Press, 2021, pp. 54–84. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctv1hm8gpd.7. Accessed 27 Mar. 2025.

Kessler, Frank. “What You Get Is What You See: Digital Images and the Claim on the Real.” Digital Material: Tracing New Media in Everyday Life and Technology, edited by Marianne van den Boomen et al., Amsterdam University Press, 2009, pp. 187–98. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt46mxjv.16. Accessed 26 Mar. 2025.

Koepnick, Lutz. “Photographs and Memories.” South Central Review, vol. 21, no. 1, 2004, pp. 94–129. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40039828. Accessed 26 Mar. 2025.

Munteán, László. “The Essay Film.” Moving Documentaries, 10 February 2025, Radboud University, Nijmegen. Lecture.

Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary. 3rd Edition, Indiana UP, 2017.