by Pia van de Schaft

Introduction

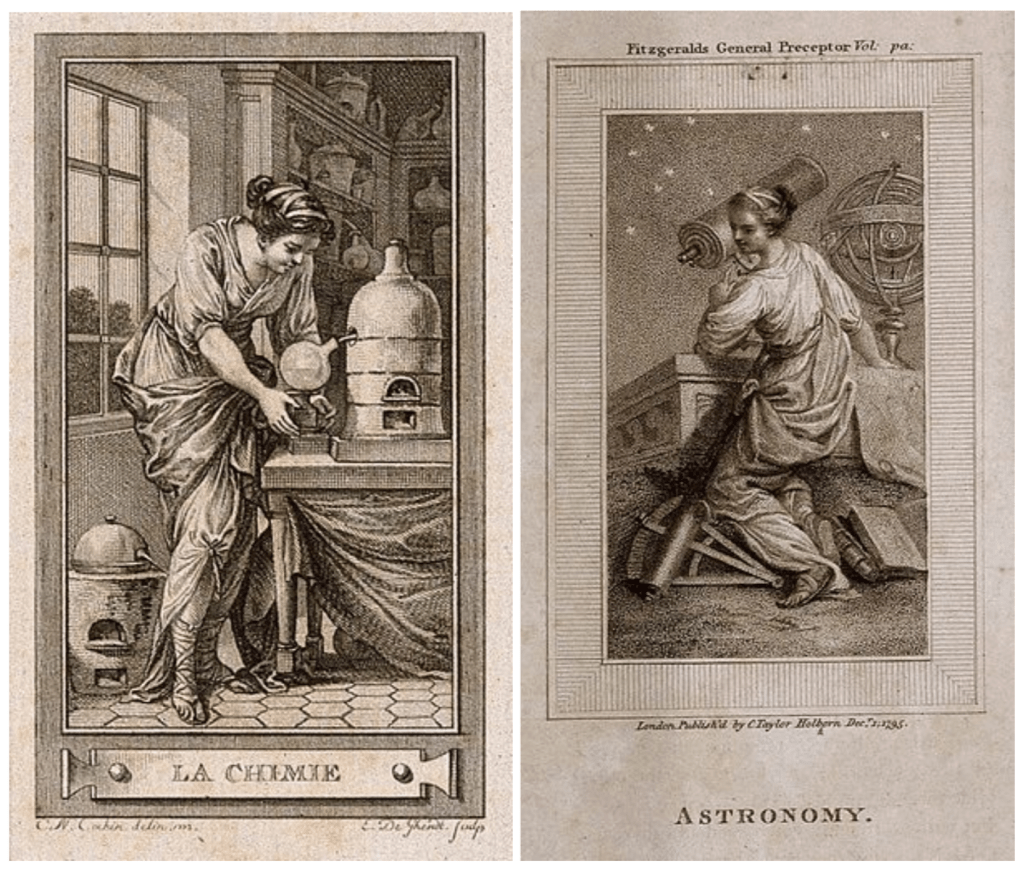

Throughout the eighteenth century, an impressive democratisation of knowledge took place in Europe. Enlightenment philosophy propagated the idea that God’s creation was comprehensible through the newly discovered laws of nature and empirical research methods. Empiricism, called ‘experimental philosophy’ at the time, became the standard in many fields of research, from physics and chemistry to the classification of plants. (The Cambridge History of Science, 2008). Such fields of study were not clearly delineated as they are today. ‘Science’ was loosely understood as knowledge of the natural world, the spread of which would lead to the betterment of society as a whole.

As a consequence of the increased appreciation of empirical research, a new scientific culture emerged. Intellectuals collaborated in national scientific academies while amateurs gathered in scientific societies of their own. Especially in Western Europe, the growing interest generated pathways for some women to engage with the sciences. The period saw the first female professors in physics and anatomy, internationally known female mathematicians and a plethora of women writers of scientific books.

Although Enlightenment thought propagated equality, the sciences retained a manly connotation. Just because the human mind was able to investigate God’s creation, that did not mean anyone was capable of such a feat. For many of the most prominent Enlightenment thinkers, it was specifically the white man that possessed the supposedly ‘rational’ and ‘civilised’ mind that critical thinking and empirical observation required. Femaleness was associated with an innate emotionality, which was incompatible with scientific research (Outram, 2019). As a result, a woman educated in the natural sciences was considered to be utterly unladylike (Findlen, 1995).

The idea that only the white man was capable of rational observation strengthened a long tradition of excluding women from scientific endeavours. Many doubted the possibility and desirability of theoretically educating women (the well-known philosopher Jean Jaques Rousseau, for example, famously argued against it). Even scientific handbooks for women were not supposed to get too complicated, as to not educate them beyond what was ‘appropriate’ for their sex. What was considered to be appropriate women’s education remained subject to debate throughout the century (Findlen & Messbarger, 2005).

Although rules to exclude women from scientific institutions would not emerge until the nineteenth century, the masculine connotation of the sciences kept most women out of scientific research. How, then, did several women become renowned scientists, rising to the top of the learned community? What other spaces did women occupy in the changing scientific culture of the eighteenth century? And how did they reconcile their participation in science with its overwhelmingly male reputation?

The existing research on eighteenth-century female intellectuals is vast, but fragmented. This article provides a broad overview of some of women’s most interesting contributions to Enlightenment science, mapping their access to scientific spaces, the roles they played in science from the home and how they could make interdisciplinary contributions to science from neighbouring disciplines.

Women in science, a public spectacle

Women at university

The first female university professors were appointed in eighteenth-century Italy. The most famous of these was Laura Bassi, an Italian physicist who taught at the University of Bologna. She was admitted into the scientific academy of the same city after she showed incredible talents for learning. At the time, scientific academies were important and prestigious institutions, membership of which symbolised a recognition of scientific capability. Pope Benedict XIV, who stood at the head of both the Catholic Church and the University of Bologna, appointed Bassi as professor of natural philosophy in 1732. This was one of many choices that would gain him a reputation as a supporter of (female) scientists (Findlen, 1993).

Generally, educated women were considered unusual. Both because they were few and far between, but also because their existence was seen as a biological and cultural anomaly. Laura Bassi was initially prohibited from teaching regularly, as it was regarded improper for a woman to teach in the sciences. Instead, she was used as a public spectacle, appearing only at special events to draw crowds to the university (Elena, 1991). And draw crowds she did. Bassi had caused a buzz across Europe and was known internationally as the ‘Minerva of Bologna’, a reference to the mythical Roman goddess of science.

The nickname suited her superhuman status. At the time, she was not seen as living proof of women’s intellectual capacities, but a unique exception to the rule. It is no surprise, then, that it took some effort for Bassi to be taken seriously as an intellectual. She pressured the university to allow her to teach regularly and even insisted on earning a salary equal to that of her male colleagues. Her arguments were strengthened by the support of pope Benedict (Logan, 1994).

After Bassi, female intellectuals were met with more scepticism from their male colleagues. The learned men of Bologna criticised the pope when he showed support for another woman, the mathematician Faustina Pignatelli. (Findlen, 2016). When yet another, Maria Gaetana Agnesi, was appointed as professor of mathematics in 1750, the support had been watered down to a purely symbolic role. Agnesi did not work at the institution, nor did she receive a salary for the position (Cavazza, 2016). It seems the learned community could allow one exceptional woman at the university, but they did not want to make a habit out of it.

Funding the sciences

But science was not only situated within university walls. Elsewhere, several women publicly aided research through other, often financial, means. The Russian tsarina Catharine financially invested in the Russian Academy of Sciences. When she was elected as head of the establishment, her predecessor had left it in a dire state. Catharine’s financial policy and clever investments allowed it to flourish. She wrote a list of fourty-five weak points of the institution’s organisation and brought the number of students from twenty-nine to eighty-nine in a single year. She used the funds they generated to invest in laboratories and botanical gardens on the premises (Gordin, 2005).

Over in England, the Duchess Margaret of Bentick gained an international reputation for investing fortunes into the collection of natural and scientific objects. She built the largest natural history collection of her country (Sloboda, 2010). Queen Charlotte of the United Kingdom also bought scientific instruments and books, gifting them to intellectuals that she kept in close contact with. Supporting a network of researchers through the donation of both objects and funds, she became an important patron of the sciences (Hansen, 2023).

Patronage of the natural sciences fit well within the spirit of the time. According to Enlightenment thought, knowledge dissemination would help society progress and evolve. Using their funds, the women took on a supporting role in this endeavour, becoming key players in the generation of scientific knowledge.

This type of financial support was sometimes specifically directed at spreading knowledge to the lower classes. The Dutch philanthropist Maria Duyst van Voorhout became famous for funding several boy’s orphanages, to bring forth a new generation of scientifically educated young men. After her death in 1754, she divided her inheritance of 500.000 Dutch guilders amongst boys’ schools in the cities of Delft, Utrecht and Gouda, which were called Fundaties van Renswoude (Roberts, 2010). She urged the schools to focus on technical education, priming the boys for careers in engineering or science, which would benefit society as a whole (De Booy, 1985).

Science for the wider public

Women with less money to spare could join scientific societies. These social gatherings, at which scientific experiments were exhibited and discussed, popped up in many European countries over the course of the century. As time went on, the rules of the once casual societies became increasingly formalised. The societies also became exclusionary through the introduction of a contribution fee, and the establishment of statutes. The number of female members declined.

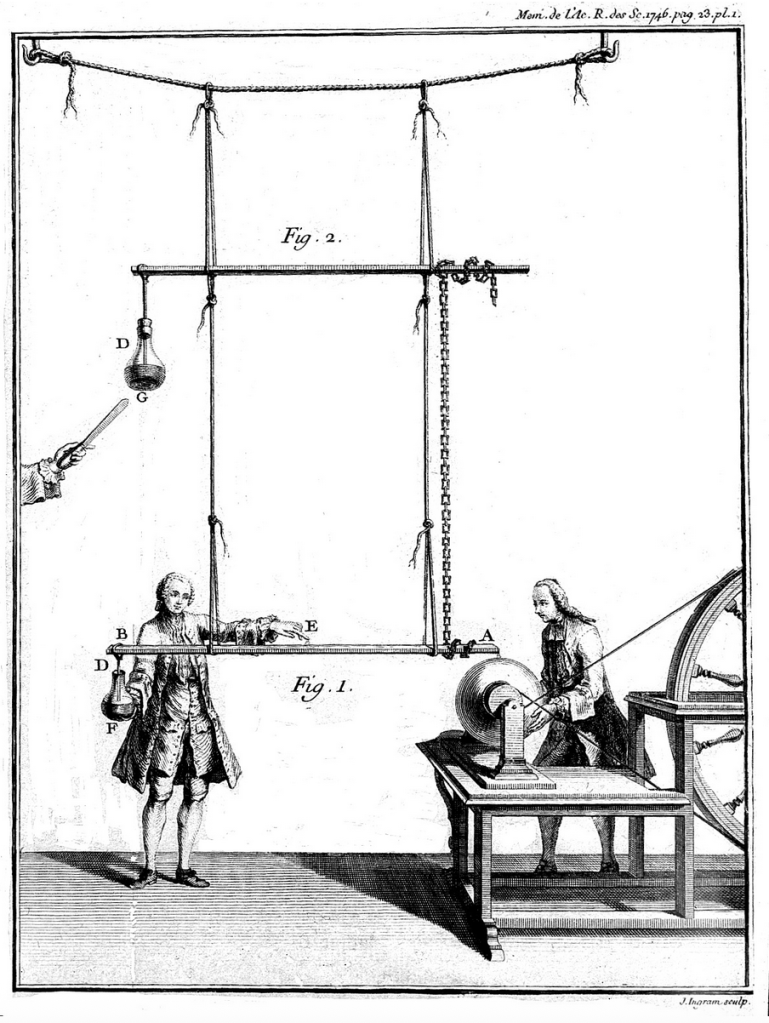

In the Dutch city of Middelburg, however, women responded with the creation of a scientific society of their own. This Natuurkundig Genootschap der Dames (Physics Society for the Ladies) was the only one of its kind. The Genootschap allowed the women to broaden their knowledge of science through visual demonstrations of experiments (Sturkenboom, 2004).

The visual experiment was considered appropriate for women because it showed complicated phenomena, such as magnetism and electricity, without requiring theoretical knowledge of their workings. A popular example was the ‘Leyden jar’, a glass invention that stored static electricity and produced shocks upon touching its surface. Using this type of invention made knowledge accessible for an uneducated audience, but did not offer a deeper understanding of science.

Nevertheless, women eagerly flocked to this surface-level scientific education. Similar practices took place at public lectures and dissections. These were spectacular exhibitions of scientific findings and human and animal anatomy. Women’s interest in these events proved to be lucrative. Many organisers included images of women in their advertisements, in an attempt to specifically attract a female audience (Roberts, 1999; Zuidervaart 1999).

Science behind closed doors

Working from home

In the eighteenth century, many scientific practices were situated in the home – from keeping insects and growing plants, to conducting experiments or building telescopes (Terrall, 2014). The kitchen often functioned as a backdrop in the history of science, as the stove was an important scientific instrument (Werrett, 2017). This private workspace was especially useful to women, who were faced with exclusion from the scientific community.

Anna Morandi Manzolini was an Italian intellectual who used her home to practice anatomy with her husband. The couple turned their house into a scientific workspace, conducting meticulous dissections and building wax sculptures that conveyed their findings. The home studio was visited by anatomists and students, which gained the couple international fame. After her husband’s death, Morandi Manzolini even continued her own career, teaching at the University of Bologna (Messbarger, 2010). The home could thus be a stepping stone to a university career in science.

Conversely, the aforementioned university professor Laura Bassi actually returned to her home to teach. When the university forbade her from lecturing in experimental Newtonian physics, one of her fields of expertise, she invited students to her home instead. There, she gained autonomy over her lectures, which once again attracted both students and colleagues (Findlen, 1993).

Whether starting out in the home or returning to it, resilient female intellectuals sought cover in the privacy of their home. The domestic sphere provided women a safe haven to shape their careers, away from the prying eyes of the public.

Invaluable assistance

In the home, female family members of scientists were also closely involved with the scientific research taking place in their living spaces (Sagal, 2022). The role of assistant seemed to flow naturally out of romantic or familiar relationships. A wife that occupied herself with the sciences, as well as the housekeeping, became increasingly desired in intellectual circles (Roberts, 2016).

The French chemist and translator Marie Lavoisier investigated oxygen and combustion with her husband Antoine. While he kept his hands busy conducting experiments in their home laboratory, Marie’s contributions ranged from taking notes to translating scientific texts for her husband. Her meticulous documentation would later become part of his publications. (Antonelli, 2022). Despite her crucial contribution to their research, the position of assistant was considered a subordinate role at the time. Only relatively recently have historians begun to appreciate both the Lavoisiers as scientists in their own right.

Women’s support of scientific endeavours can even be found outside of the laboratory. Many male scientists’ careers depended on the free time they gained by leaving childrearing and housekeeping to female family members. Take the mathematician Leonard Euler (founder of the field of calculus) who went blind over the course of his career but became increasingly productive. It is not hard to imagine who made this productivity possible; when his wife Katharina Gsell died, he married her sister quickly thereafter to avoid burdening the children with his care (Gautschi, 2008). It is likely that the trajectory of the history of science depended on many women like the Gsells, who facilitated their husbands research by providing them with care and housekeeping.

The relative invisibility of assistants provided them with space to research, but complicated their relationship with science. When the Royal Irish Academy presented the German astronomer Caroline Herschel with an honorary membership, she hesitated to accept. She was educated in maths and astronomy, participated in the research of her brother William Herschel and spotted eight new comets by herself. Nevertheless, she insisted she was only an assistant who, thanks to her female sex, should not be considered a true scientist. Reducing herself to a supporting role may be an honest reflection of her personal beliefs, but could also have been a tactic to avoid criticism for her scientific interests (Winterburn, 2015).

Women of letters

The growth of the eighteenth-century scientific community coincided with the flourishing of an international correspondence network, which was named the ‘Republic of Letters’ by contemporaries. In this metaphorical republic, ‘men of letters’ exchanged knowledge freely without fearing censorship of a monarch or church (Irving-Stonebraker, 2014).

Letter-writing was a popular pastime to girls and women in the eighteenth century (Caine et al., 2023). Though research on the topic is sparse, women also actively participated in scientific correspondence. This is perhaps best illustrated by the work of one eighteenth-century historian, Jacob Brucker, who attempted to document the Republic of Letters through a series of portraits. He set out to create an accurate reflection of the learned community, and thus included several female intellectuals in his project (Van Deinsen, 2024).

The letters of the Italian translator and mathematician Maria Angela Ardinghelli were even read aloud at the Paris Academy of Science. She corresponded with one of the members, the French physicist Jean-Antoine Nollet, and informed the French intellectuals about scientific developments in her country. Her letters thus bridged the gap between the two scientific communities, which fed scientific debates at the time (Bertucci, 2013).

Some historians have even termed female scientist’s correspondence ‘letter laboratories’, functioning as spaces where they workshopped theories and interacted with colleagues in their field (Bonnel, 2000). Because they were circulated by postage as well as oral recital, letter-writing allowed women to take part in scientific debates.

Blurring borders

Popular science and education

Women did not only write, but also published about the natural sciences. An especially interesting field in which women were active was the emerging field of popular science. It was deemed especially appropriate for women writers, as it had an educational and pedagogical objective.

Maria Jacson, an English author of botanical books for women and children, wrote a handbook about Carl Linneaus’ classification of plants. While writing handbooks already required ample knowledge of the scientific field, the author also cited prominent authors and engaged with scientific debates of her time (Shteir, 1990). Though the publication was intended for a lay audience, it allowed Jacson to develop and share her expertise on the natural world.

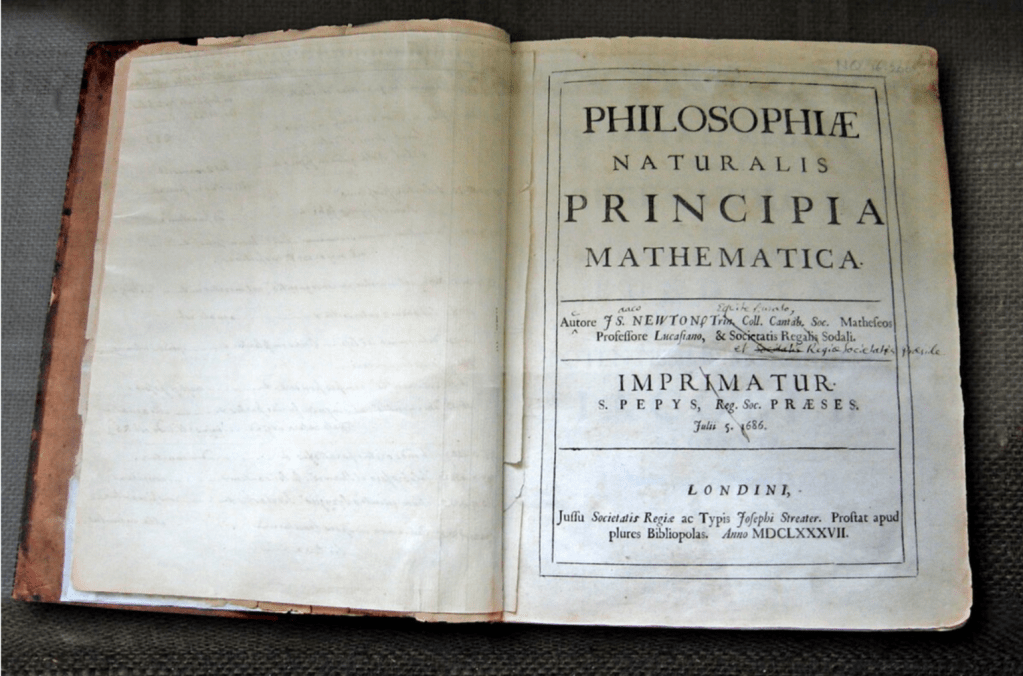

While some women sprinkled new insights into handbooks, others published entirely novel theories under the guise of creating educational materials. The French noblewoman Émilie du Châtelet wrote a scientific handbook for her son. In this work, she reconciled Isaac Newton’s theories of physics with the field of metaphysics, which had been pioneered by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz the century before. In true eighteenth-century fashion, the work spanned a wide range of philosophical and scientific themes, ranging from space and matter to the existence of God. The work sparked such debate in the scientific community, that she published a revised version only two years later (Zinnser, 2001). It even earned Du Châtelet a reputation as a renowned mathematician and physicist.

Similarly, the Italian mathematician Maria Gaetana Agnesi wrote the first comprehensive overview of the field of calculus, the most complicated branch of mathematics at the time. While she maintained the book was only intended for young students to gain an understanding of the field, it also earned her a position at Bologna’s university.

Agnesi’s case provides an interesting insight into female intellectuals’ choice to term their theories as educational materials. Towards the end of her life, she gave up her career in mathematics to pursue caring for the sick and elderly. She argued that her intellectual interests had been a way to understand God’s creation and spent the last years of her life in service to others. According to Agnesi, this was a much better way of bringing glory to God than mathematics had ever been (Mazotti, 2001). Living her last years in poverty, she seems to have been deeply convinced by her calling of servitude.

It remains unclear if the pedagogical or spiritual motives underpinning female intellectuals’ works were simply a cover for their scientific pursuits, or if they truly believed the serving and education of others to be their true calling.

Female translators

Many other female writers were active in the field of translation. It was the perception of translators as transmitters of pre-existing knowledge that offered some women leeway to publish about science freely. Female chemist Claudine Picardet, for example, aided the international exchange of knowledge by translating chemistry research papers from Swedish to French. Just like many other female translators of scientific publications, she was involved in the scientific community and even conducted her own experiments (Bret, 2016).

Possibly the most famous scientific translation of the period was published by a woman. Emilie du Châtelet translated Isaac Newton’s laws of motion and gravity, a work known as Principia Mathematica, and supplemented it with theories by leading mathematicians. Finally, she added her own commentary. This resulted in the most comprehensive translation of the work to date, which aided in the spread of Newtonian physics throughout Europe. It remains the standard French translation to this day (Zinsser, 2001).

The previously mentioned mathematician Maria Angela Ardinghelli also became famous for her translations of scientific works. She published an Italian translation of English research into blood vessels. She initially worked from an existing French translation but, after finding out it contained errors, also studied the English one. In order to complete her translation, she completely recreated the original experiments. Her final publication even contained ample criticism of the French translator’s errors. Because her experiments were sound and her additions were valuable, Agnesi’s comments were met with praise.

It seems that, in Ardinhelli’s case, the visibility did come at a cost. Later in her career, she transitioned into publishing anonymously. It has been theorised that the anonymity served to guard her from criticism about her female identity and scientific interests. (Bertucci, 2013). Recognition of translators’ scientific knowledge could thus also prove a burden.

Artistic endeavours

Illustration was another important medium for conveying empirical research. The French anatomist Marie-Genevieve-Charlotte Thiroux d’Arconville, for example, caused a stir when she published an illustration of the male and female skeleton in 1759. She incorrectly depicted the female skeleton with a significantly smaller skull and larger hipbone than the men’s. The work was taken as proof that women were destined for motherhood, rather than rational thinking (Schiebinger, 1987).

While art could be intertwined with scientific research, it was also considered to be a separate discipline. When Maria Morandi Manzolini made wax figures, these were considered educational materials as well as works of art. Consequently, she was admitted to both the Academy of Arts and the Academy of Science (Messbarger, 2010). This distinction is crucial, when considering that it may have been easier to engage with art from the home, than it was for women to join the scientific community. Female artists thus, sometimes, found their way into science through artistic disciplines.

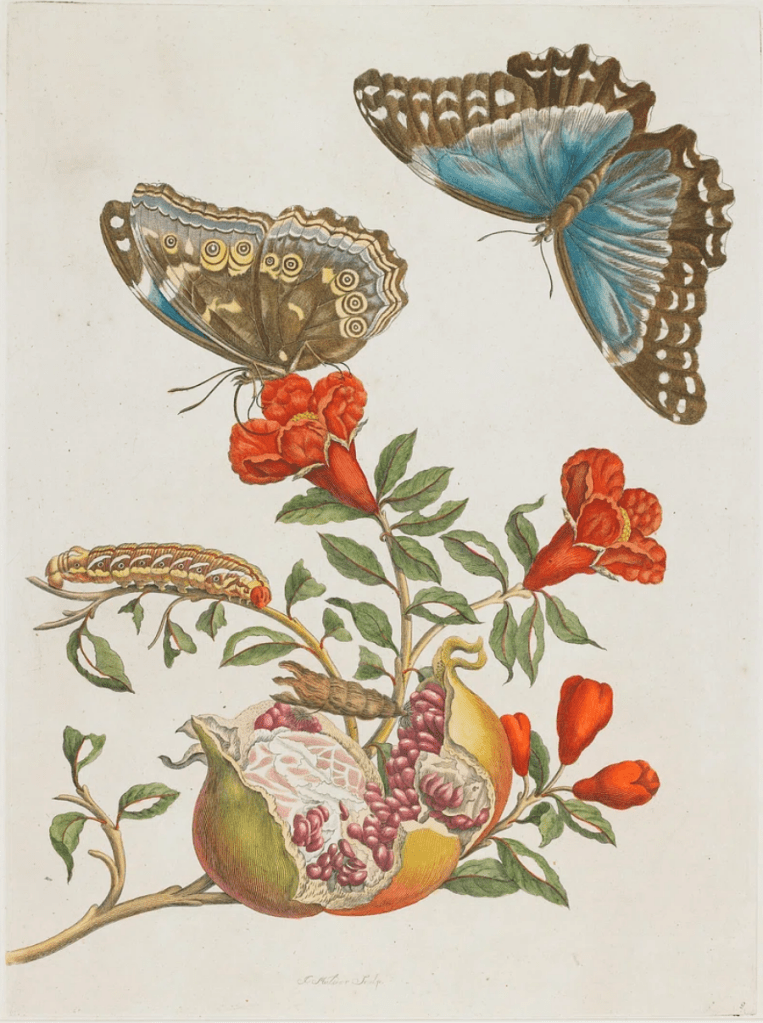

The most influential of these was Maria Sybilla Merian, a German woman who studied insects and plants. At the start of the eighteenth century, she travelled to Surinam with one of her daughters to study the local flora and fauna. Upon returning to Europe, and settling in The Netherlands, she made a series of detailed illustrations of insects and plants. In collaboration with her daughters, she compiled these in a book that would make her famous in the European scientific community.

Merian is widely considered to have laid the groundwork for the field of ecology. At a time when many were busy researching the differences between plants and animals (the practice of taxonomy was particularly booming in the eighteenth century) she depicted how insects and plants interact in nature. Her artistic depictions not only showed insects previously unknown to Europeans, but also emphasised symbiosis in nature. Through her artistic depiction of metamorphosis, she furthermore refuted the popularly held belief that butterflies generated spontaneously (Pieters & Winthagen, 1999; Reitsma, 2008). Though she held no reputation as a scientist, her art contributed new insights to the scientific debates of her time.

Conclusion

Some eighteenth-century women were notably prominent in the European scientific community. Appearing before lecture halls and publishing their own scientific research, these intellectuals publicly presented themselves as experts in their fields. Interestingly, their success did not disprove the commonly held belief that women were unfit to study the sciences. The women were seen as exceptional or even freaks of nature, and their genius as highly unusual.

Supported by the emerging idea that knowledge should be disseminated to spread Enlightenment and progress, women also found ways to indulge their scientific interests outside of scientific institutions. Taking part in a wider scientific culture, the women generated new knowledge in a plethora of disciplines. Many avoided laying claim to intellectual authority, which may have been necessary to preserve their feminine reputation.

The period’s most famous case studies show that women’s scientific interests challenged eighteenth-century gender roles, questioning their supposedly limited intellectual capacity. At the same time, adhering to some expectations of femininity could protect them from criticism and evade rejection from the scientific community. From a gray area in the eighteenth-century gender roles, the women made indispensable contributions to the history of knowledge.

Pia van de Schaft is a historian interested in the history of ideas about gender diversity in the Early Modern period, currently completing a Research Master’s Historical Studies at Radboud University. This article is based on research conducted within Radboud Honours Academy under the wonderful guidance of Dr. Anne Petterson and Dr. Eleá de la Porte.

Sources

Antonelli, F. (2022). Note-taking and Self-promotion: Marie-Anne Paulze-Lavoisier as a Secrétaire (1772–1792). In F. Antonelli, A. Romano and Paolo Savoia (Eds.), Gendered Touch Women, Men, and Knowledge-making in Early Modern Europe (pp. 220–244). Brill.

Bertucci, P. (2013). The In/visible Woman: Mariangela Ardinghelli and the Circulation of Knowledge between Paris and Naples in the Eighteenth Century. Isis, 104(2) 226-249. https://doi.org/10.1086/670946

Bonnel, R. (2000). La correspondence scientifique de la marquide Du Châtelet: la ‘lettre-laboratoire’. In A. Strugnell and J. Goffen (Eds.), Femmes en toutes lettres Les épistolières du XVIIIe siècle (pp. 79–95). Voltaire Foundation.

Bret, P. (2016). The letter, the dictionary and the laboratory: translating chemistry and mineralogy in eighteenth-century France. Annals of Science, 73(2), 122-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/00033790.2015.1034780

Caine, B., C. Monagle, C. James and D. Garrioch. (2023). The Rise of the Familial Letter. In ibidem (Eds.), European Women’s Letter-writing from the 11th to the 20th Centuries (pp. 130-194). Routledge.

Cavazza, M. (2016). Benedict’s Patronage of Learned Women. In: R. Messbarger, C.M.S. Johns and P. Gavitt (Ed.), Benedict XIV and the Enlightenment: Art, Science, and Spirituality (pp. 18). University of Toronto Press.

De Booy, E.P. (1985). Van erfenis tot studiebeurs: de Fundatie van de vrijvrouwe van Renswoude te Delft: opleiding van wezen tot de ‘vrije kunsten’ in de 18de en 19de eeuw. De fuddatiehuizen. Bursalen in deze eeuw. Historische Vereniging Holland.

Elena, A. (1991). “In lode della filosofessa di Bologna”: An Introduction to Laura Bassi. Isis, 83(3), 510-518. https://www.jstor.org/stable/233228

Findlen, P. (1993). Science as a Career in Enlightenment Italy: The Strategies of Laura Bassi, Isis. 84(3), 441-469. https://www.jstor.org/stable/235642

Findlen, P. (1995). Translating the New Science: Women and the Circulation of Knowledge in Enlightenment Italy. Configurations, 3(2), 167-206. https://doi.org/10.1353/con.1995.0013

Findlen, P. & Messbarger, R. (2005). The contest for knowledge: debates over women’s learning in eighteenth-century Italy. University of Chicago Press.

Findlen, P. (2016). The Pope and the Englishwoman: Benedict XIV, Jane Squire, the Bologna Academy, and the Problem of Longitude. In: R. Messbarger, C.M.S. Johns and P. Gavitt (Ed.), Benedict XIV and the Enlightenment: Art, Science, and Spirituality (pp. 40-73). University of Toronto Press.

Gautschi, W. (2008). Leonhard Euler: His Life, the Man, and His Works. SIAM Review, 50(1) (2008) 3-33. https://doi.org/10.1137/070702710

Gordin, M.D. (2005). Arduous and Delicate Task: Princess Dashkova, The Academy of Sciences, and the Taming of Natural Philosophy. In: S.A. Prince (Ed.), The Princess & the Patriot: Ekaterina Dashkova, Benjamin Franklin, and the Age of Enlightenment (pp. 9-14). American Philosophical Society.

Hansen, M. (2023). Queen Charlotte’s scientific collections and natural history networks. Notes and Records, 77(2), 323-336. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsnr.2021.0070

Irving-Stonebraker, S. (2014). Public Knowledge, Natural Philosophy, and the Eighteenth-Century Republic of Letters. Early American Literature, 49(1), 67-88. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24476587

Logan, G.B. (1994). The Desire to Contribute: An Eighteenth-Century Italian Woman of Science, The American Historical Review, 99(3) 785-812. https://doi.org/10.2307/2167770

Mazzotti, M. (2001). Maria Gaetana Agnesi: Mathematics and the Making of the Catholic Enlightenment. Isis, 92(4), 657-683. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3080337

Messbarger, R. (2010). The Lady Anatomist: The Life and Work of Anna Morandi Manzolini. The University of Chicago Press.

Outram, D. (2019). The enlightenment. Cambridge University Press.

Pieters, F. F. J. M., & Winthagen, D. (1999). Maria Sibylla Merian, naturalist and artist (1647-1717): a commemoration on the occasion of the 350th anniversity of her birth. Archives of Natural History, 26(1), 1-18.

Reitsma, E. (2008). Maria Sibylla Merian & dochters: Vrouwenlevens tussen kunst en wetenschap. WBOOKS.

Roberts, L. L. (1999). Going Dutch: Situating Science in the Dutch Enlightenment. In W. Clark, J. Golinski and S. Schaffer (Eds.), The Sciences in Enlightenment Europe (pp. 350–388) The University of Chicago Press

Roberts, L.L. (2010). Instruments of Science and Citizenship: Science Education for Dutch Orphans During the Late Eighteenth Century. Science & Education, 21, 167-173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11191-010-9269-4

Roberts, M. K. (2016). Sentimental savants: philosophical families in Enlightenment France. The university of Chicago Press.

Sagal, A., (2022). Botanical entanglements: Women, Natural Science, and the Arts in Eighteenth-Century England. University of Virginia Press.

Schiebinger, L. (1987). Skeletons in the Closet: The First Illustrations of the Female Skeleton in Eighteenth-Century Anatomy. In C. Gallagher an T. Laqueur (Eds.), The Making of the Modern Body: Sexuality and Society in the Nineteenth Century (pp 42-82). University of California Press.

Sturkenboom, D. (2004). De elektrieke kus : over vrouwen, fysica en vriendschap in de 18de en 19de eeuw : het verhaal van het Natuurkundig Genootschap der Dames in Middelburg. Augustus.

Shteir, A. B. (1990). Botanical Dialogues: Maria Jacson and Women’s Popular Science Writing in England. Eighteenth-Century Studies 23(3), 301-317. https://doi.org/10.2307/2738798

Sloboda, S. (2010). Displaying Materials: Porcelain and Natural History in the Duchess of Portland’s Museum. Eighteenth-Century Studies, 33(4), 455-472. https://www-jstor-org.ru.idm.oclc.org/stable/40864418?seq=4

Terrall, M. (2014). Catching Nature in the Act: Réamur and the Practice of Natural History in the Eighteenth Century. The University of Chicago Press.

The Cambridge History of Science. (2003). Cambridge University Press.

Van Deinsen, L. (2024). Female Faces in the Fraternity. Printed Portraits Galleries and the Construction and Circulation of Images of Learned Women in the Republic of Letters. In M. Bolufer, L. Guinot-Ferri and C. Blutrac (Eds.), Gender and Cultural Mediation in the Long Eighteenth Century. New Transculturalisms, 1400–1800 (pp. 123-149). Springer Nature.

Werrett, S. (2017). Household Oeconomy and Chemical Inquiry. In S. Werrett, L.L. Roberts (Eds.), Compound Histories Materials, Governance and Production, 1760-1840 (pp. 35-56). Brill.

Winterburn, E. (2015). Caroline Herschel: Agency and Self-Representation. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, 69(1), 69-83. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsnr.2014.0060

Zinsser, J. P. (2001). Translating Newton’s ‘Principia’: The Marquise du Châtelet’s Revisions and Additions for a French Audience. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, 55(2), 227-245. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsnr.2001.0140 Zuidervaart, H. J. (1999). Van ‘konstgenoten’ en hemelse fenomenen. Nederlandsche sterrenkunde in de achttiende eeuw. Erasmus Publishing.