by Marle Zwietering

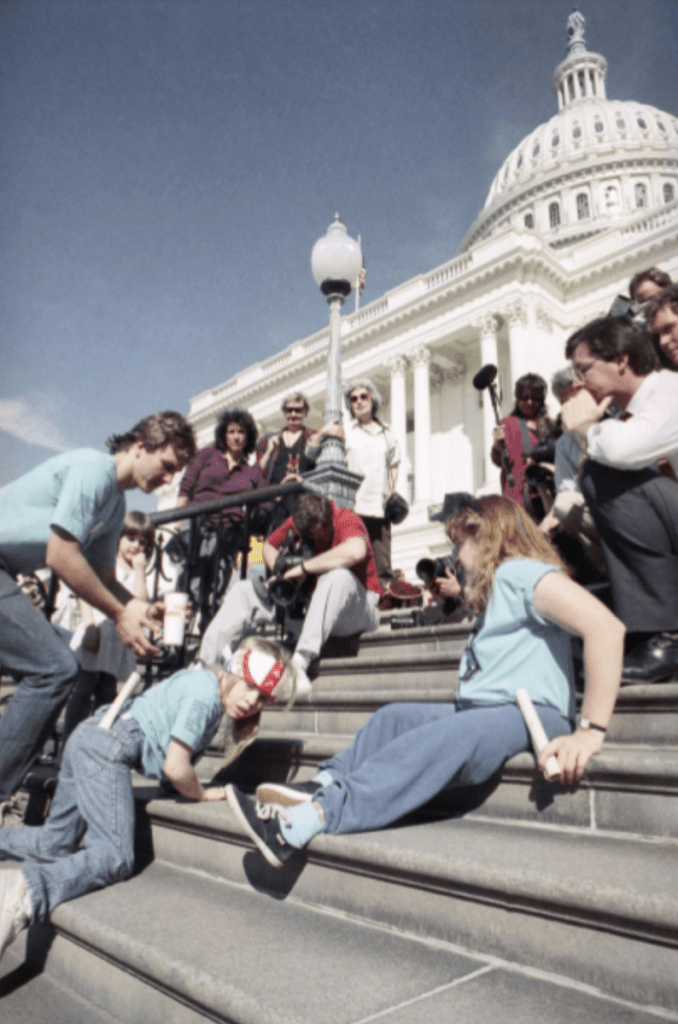

In 1990, over sixty activists of disability rights organization ADAPT left their mobility aids at the bottom of the stairs of the United States Capitol. They then ascended the stairs in a protest now known as the Capitol Crawl. They advocated for the passing of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), a law that requires barrier-free access for people with disabilities in the streets and public buildings of the city (Ginsburg and Rapp 704). One of the protesters was eight-year-old Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins, whose cerebral palsy caused paralysis in her legs. In video footage made at the Capitol Crawl, Keelan-Chaffins is visibly struggling to crawl to the top of the stairs while saying “I’ll take all night if I have to” (Litowsky 08:37-08:40, see fig. 1).

Fig. 1: Litowsky, Linda. “U.S. Capitol Crawl: Wheels of Justice Action.” Vimeo, posted by Stephanie K. Thomas, 3 April 2019, https://vimeo.com/328233990, 08:38 min.

Through photographs and Litowsky’s video footage, Keelan-Chaffins became a national symbol for disabled Americans’ fight for inclusion in the media (Hackenesch 2, see fig. 2). She had participated in protests before and continues her work as a disability rights activist to this day. Thirty years after the Capitol Crawl, the artist Gina Vernon and Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins collaborated on their sculpture All the Way to Freedom to commemorate the passage of the ADA and the Capitol Crawl (see fig. 3, 4). The artwork is made with Vernon’s signature technique of draping quickly hardening fabric over a live posed model and painting the sculpture afterward. In this essay, I will analyze how the Capitol Crawl is commemorated in Gina Vernon’s All the Way to Freedom by using the concept of durational disability aesthetics.

Durational Disability Aesthetics

The model of durational aesthetics provides a way to think about how images behave over time and how certain forms of representation can show how time has elapsed (Weissman 298). Terri Weissman argues that all the objects that fit into the model of durational aesthetics and are made over time about a specific object or person, are made by one artist. However, I argue that durational aesthetics can also be applied to artworks by different artists about the same person, in this case Keelan-Chaffins, during different parts in this person’s life. Additionally, Tobin Siebers explains aesthetics as tracking “the sensations that some bodies feel in the presence of other bodies” (1). He coined the concept “disability aesthetics” to emphasize the presence of disability in the tradition of aesthetic representation. Disability aesthetics “refuses to recognize the representation of the healthy body- and its definition of harmony, integrity, and beauty – as the sole determination of the aesthetic. Rather, disability aesthetics embraces beauty that seems by traditional standards to be broken, and yet is not less beautiful, but more so, as a result” (3). I will combine durational and disability aesthetics into “durational disability aesthetics”, which emphasizes how society interacts with disabilities over time, how the representation of disability changes over time, and how people with disabilities are always a part of our society.

Durational disability aesthetics is important because disability has often been avowed as shameful or tragic and people with disabilities are frequently hidden away in segregated schools, asylums, hospitals, and nursing homes (Garland-Thomson, Staring 19). Smith argues that this is as though “more than two disabled people in the same room will start a riot or make everyone feel awkward” (272). By hiding disability away, people feel stunned and alienated when they do see people with disabilities (Garland-Thomson, Staring 20). Additionally, it makes it seem like accommodations in public spaces are unnecessary because disabled people who need the accommodations are barely visible in public. It is therefore important that artworks show people with disabilities of all ages, backgrounds, and body types. In this essay, I will argue that Gina Vernon’s All the Way to Freedom is an example of durational disability aesthetics that combines individual and collective memory and experiences of people with disabilities.

Collective Memory and Action: The Problem with Accessibility

The Capitol Crawl is part of the collective memory of many American people with disabilities. Collective memory can be defined as how “social groups store, remember, and transmit their knowledge and experiences” (Melianto and Syamsudin 74). Furthermore, it helps social groups to “maintain their identity, strengthen their sense of solidarity, and give meaning to shared experiences” (Melianto and Syamsudin 74). The Capitol Crawl was an important event for disability rights activists.

Fig. 2: Markowitz, Jeff. “Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins at the Capitol Crawl.” March 12 1990, photograph. ABC News, https://abcnews.go.com/US/30th-anniversary-disability-civil-rights-protest-advocates-push/story?id=69491417.

They came together to fight for their right to accessible public spaces, despite the large variety of disabilities and struggles with accessibility. As Keelan-Chaffins writes:

We discovered that despite our differences in how we view our disability or what form or action our disability advocacy takes, we are a powerful community! 34 years later we need to join together again- to save our democracy and support all civil rights laws and preserve the ADA. This is why our work is not finished. And why we must continue to work together.

Vernon’s artwork enabled Keelan-Chaffins to spread the message that the fight for accessibility is not over yet (Vernon, “Freedom”), and strengthen the solidarity between people with disabilities who experience the consequences of inaccessible public spaces. Because able-bodiedness is seen as “normal”, it becomes introduced into life as compulsory able-bodiedness (McRuer 370). While few people fit the ideal of an able body and disability can occur at any time, it is still expected of all people to aim for this impossible and unattainable ideal (Goffman 129). As Garland-Thomson writes, “people deemed disabled are barred from full citizenship because their bodies do not conform with architectural, attitudinal, educational, occupational, and legal conventions based on assumptions that bodies appear and perform in certain ways” (Extraordinary Bodies 46). The accommodations of the ADA emphasize that disability is one of the many differences among people and that society should adjust the public environment accordingly (Garland-Thomson, Extraordinary Bodies 49). The activists made the inaccessibility of the city visible by showing that the stairs of the Capitol are inaccessible to those who need mobility aids. Moreover, the Capitol houses the Unites States Congress; pointing out it’s inaccessibility can also be seen as a metaphor for the systematic erasure of people with disabilities in political society.

Furthermore, seeing an “unexpected body”, one that does not conform to people’s expectations, attracts stares (Garland-Thomson, Staring 37). Disabled bodies cause staring because they are unpredictable or indecipherable to non-disabled people (38). This puts disabled people in an uncomfortable situation because they have to assert their dignity, and makes starers uncomfortable because they struggle with whether to look or look away (Garland-Thomson, Staring 84). However, during the Capitol Crawl, the disability rights activists used this to their advantage, forcing people to watch and listen.

Fig. 3: Vernon, Gina. All the Way to Freedom, 2019, fabric sculpture, Denver, Prism workspaces studio. JKC Legacy, https://jkclegacy.com/blog/celebrating-the-31st-anniversary-of-the-capitol-crawl-march-12-2021.

In Vernon’s artwork, the viewers are invited to stare at Keelan-Chaffins’s body in a pose that replicates her crawling up the Capitol stairs. Because Keelan-Chaffins’s face in the artwork is invisible, the viewer can look at her disabled body without feeling like Keelan-Chaffins is staring back at them. The person with disabilities, in the artwork, is thus not put in the uncomfortable position of being stared at. Furthermore, seeing disabled people represented in art like this can expand the viewer’s vision of human variation and difference, and increase the acceptance of disabled people in public (Siebers 3).

Additionally, the artwork “portrays a person with disabilities caught both between the attitudinal and physical obstacles faced by persons with disabilities despite the efforts of the ADA to remove them” (Vernon, “Fighting”). The chain that is draped across Keelan-Chaffins’s body is a visual metaphor for disabled people who are chained down by inaccessible surroundings. This is further emphasized by the fabric draped over Keelan-Chaffins’s body which seems to pin her down, unable to give her the freedom to move around. This feeling of being frozen in time, of accessibility not being improved upon enough, is further exemplified by the use of the hardened fabric material; Keelan-Chaffins seems to be stuck in place, unable to move forward. The creative process of hardened fabric also serves as a reminder of the challenges of living with disability (Vernon, “Fighting”). Keelan-Chaffins had to go up four flights of stairs to Vernon’s studio and prepare for potential body spasms or an asthma attack during the creation of the sculpture (Vernon, “Fighting”). The hardened fabric that allowed Vernon to mold Keelan-Chaffins’s body accurately was also restricting her and indeed caused an asthma attack during the creation of the sculpture. By sharing the process, Vernon emphasizes that accessibility is an issue in all parts of life; even during the creation of art.

Fig. 4: Vernon, Gina. All the Way to Freedom, 2019, fabric sculpture, Denver, Prism workspaces studio. JKC Legacy, https://jkclegacy.com/blog/all-the-way-to-freedom-nownbsp.

While the ADA was passed after the Capitol Crawl, some unintended consequences caused more issues with disabled people finding employment. Because employers were forced to accommodate employees with disabilities by law, fewer people with disabilities were hired. Employers were indeed often unable to, or unwilling to, pay for the mandatory accommodations (Deleire 23-24). Furthermore, employees with disabilities could now persecute employers who did not provide necessary accommodations, causing fear of litigation by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (Deleire 21). Vernon captures this ongoing struggle for justice and equality for people with disabilities by showing that despite the passing of the ADA, Keelan-Chaffins is still restricted by chains. While the Capitol Crawl is still part of the collective memory of disabled people as a life-changing moment of activism due to the implementation of the ADA a few months later, the artwork shows that it might not have had the intended consequences by calling attention to the struggles that people still face despite the ADA. This shows that collective memories can change over time due to cultural, social, and political influences (Melianto and Syamsudin 74).

However, the artwork also shows hope for a better future. Keelan-Chaffins is reaching upwards, towards a better future. She is moving away from the inaccessible steps and chains that are trying to hold her down. This hopefulness is further highlighted by the title, All the Way to Freedom. It emphasizes that the fight for accessibility will continue until disabled people are just as free to move around as non-disabled people. The ongoing nature of this fight is an important part of the durational disability aesthetics of the artwork; the collective memory of the Capitol Crawl is depicted while the unintended consequences for the collective group of people with disabilities are also captured in Vernon’s artwork.

Individual Memory: Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins as Disability Rights Activist

According to Weissman, a key element of durational aesthetics is “to capture historical change or movement through the dialectical interplay of stillness and motion such that change is represented through the depiction of its opposite” (298). In Litowsky’s video footage and the news photographs made during the Capitol Crawl, Keelan-Chaffins is shown crawling up the stairs as a child (see fig. 1, 2). In her book All the Way to the Top: How One Girl’s Fight for Americans with Disabilities Changed Everything (2020), the cover depicts a drawing of her as a little girl climbing the Capitol stairs (see fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Pimentel, Annette Bay. All the Way to the Top: How One Girl’s Fight for Americans with Disabilities Changed Everything. Pictures by Nabi H. Ali, foreword by Jennifer Keelan-Chaffins, Sourcebooks Explore, 2020. Amazon, https://www.amazon.com/All-Way-Top-Disabilities-Everything/dp/1492688975.

In Vernon’s artwork, Keelan-Chaffins is finally represented as an adult. While there are still references to the Capitol Crawl, such as the steps on the right and the bandana around her head that she wore at the time, the artwork also focuses on her current experience with her disability. Litowsky’s video, the photographs of the Capitol Crawl, the drawing on Keelan-Chaffin’s book, and Vernon’s artwork together shape the durational disability aesthetics. Keelan-Chaffins’s media attention had been presented as problematic by some disabled activists, as “her youth invited a reproduction of the paternalistic, infantilizing view of disabled persons that is already deeply pervasive in our culture” (Hackenesch 7). By depicting Keelan-Chaffins as an adult, Vernon prevented this infantilization and showed that being disabled is part of all ages. This transformation of Keelan-Chaffins as a disability rights activist from child to adult is a key part of the durational disability aesthetics in the artwork.

In disability studies and representation, race and ethnicity are often overlooked; mostly white disabled people are represented or given a platform (Bell 278). In Litowksy’s video footage of the Capitol Crawl, the persons with speaking power are all white disabled men and the only disabled people of color that are shown remain nameless and voiceless (Hackenesh 6-7). Vernon continues this by only showing the story of a white disability activist. Furthermore, the ADA covers disabilities of both physical and mental impairments, but the disabled people who are most often seen and thought of as disabled, are people with mobility, vision, or hearing impairments (Deleire 22). However, research later revealed that those who were most negatively affected by the ADA were young, less-educated, and mentally disabled men (Deleire 22). Thus, there is a discrepancy between disabled people who are represented in daily life and the media and those who are most affected by the implementation of the ADA and the lack of accessibility in daily life, which Vernon’s art also plays into.

Conservative evangelicals were opposed to the ADA because of the protection it offered people with HIV; they associated HIV with homosexuality, which they were ideologically against (Milden 506). This objection and the discrepancy in media representation show that disability rights are intertwined with the rights of other marginalized social and political identities. Vernon’s decision to give a platform to Keelan-Chaffins again instead of disability activists of color, non-heterosexual disabled people, or people with invisible disabilities perpetuates the problem that white disability activists with visible disabilities get more attention, while those who are also affected and intersectionally marginalized due to other social and political identities, remain invisible.

The Capitol Crawl made an impact precisely because it was not one individual, but a collective group of people with disabilities who protested together. The protest highlighted the political/relational model of disability, where disability is seen as a problem of built environments and social patterns “that exclude or stigmatize particular kinds of bodies, minds, and ways of being” (Kafer 6), as opposed to the medical/individual model that emphasizes disability as an individual problem that needs to be treated or solved (Kafer 5). In the artwork, Vernon decided to show only one disability rights activist. This individual approach seems to perpetuate the idea that the struggle depicted in the artwork is Keelan-Chaffins’s individual struggle instead of a larger social struggle with inaccessibility. Vernon intended to show that civil rights are universal and that “regardless of ethnicity, gender identity, age, or politics, disability affects everyone sometime in our lives” (Vernon Freedom). Arguably, if her intention was to show that disability rights are universal rights, Vernon could have depicted multiple people from different backgrounds.

However, Keelan-Chaffins’s back is turned away from the viewer in the artwork, her face and skin color are invisible, and her disability is not obviously visible. During the Capitol Crawl and in the artwork, her mobility aids were cast aside; the round shape on the left of the artwork represents a wheelchair wheel. Keelan-Chaffins kept her leg braces on, but they are hardly recognizable in the artwork due to the folds of the hardened fabric on top. Because her disability is barely visible at first sight, the artwork could more easily represent people with all types of disabilities. Those who remember the images of Keelan-Chaffins with the bandana will recognize her, while those who do not could imagine other people with various disabilities being depicted.

Furthermore, monuments often refer to acts that have enforced power, such as war or colonialism; frequently these acts of power are commemorated by depicting white men (Millett-Gallant 36-39). Women’s bodies in public monuments are usually allegorical and serve as decorative objects (Millett-Gallant 39). By showing that a disabled person is a worthy subject of a monument to commemorate the Capitol Crawl, Vernon showed the aesthetic value of disability. Additionally, commemorating a female disability rights activist, instead of an able-bodied man, diversifies what monuments can be, who can be depicted, and what events are worthy of being commemorated. While Vernon did not give a platform to disabled people of color, non-heterosexual disabled people, or people with an invisible disability, the sculpture breaches the boundaries between Keelan-Chaffins’s personal experience as a disabled person and the public experience of all people with disabilities by allowing people to imagine people with various disabilities in the artwork and commemorating a woman with disabilities in a monument.

Conclusion

Artworks containing durational disability aesthetics are an important way to show how people with disabilities can struggle their entire lives with issues like accessibility; Vernon’s All the Way to Freedom calls attention to this and urges society to accommodate individuals with disabilities. The Capitol Crawl was a unique protest because dozens of people with various disabilities came together to fight for their rights by showing how inaccessible the city was. They used their bodies to attract stares and consequently the attention of those who could implement the ADA. By using the metaphorical chain and the inaccessible hardened fabric material, Vernon captured the unintended consequences of the ADA, while still emphasizing the hope for a better future. Consequently, the artwork commemorates the Capitol Crawl as a successful coming together of disability activists, because the ADA was implemented months later, while still emphasizing that the fight for accessible public spaces is not over yet. As Smith argues, spaces for people with disabilities are needed because “as long as claiming our own ground is treated as an act of hostility, we need our ground” (274).

Vernon also captured Keelan-Chaffins’s journey from a child to an adult disability rights advocate, which is an important aspect of the durational disability aesthetics in the artwork. However, this means that disabled activists of color, non-heterosexual disabled activists, and activists with invisible disabilities, who did not get a voice then, still do not get a voice now in this artwork. While Vernon intended to represent people with disabilities from all ethnicities, genders, ages, or politics, she only showed a white disability rights activist with a visible disability. Durational disability aesthetics is useful to analyze the representation of disability over time. In Litowsky’s video, only white disability rights activists got a voice, which is perpetuated in Vernon’s artwork. Despite this, due to the invisibility of Keelan-Chaffins’s face, skin color, and disability, the viewer is still able to imagine people with all kinds of disabilities being represented in the artwork. Furthermore, by creating a monument of a disabled woman, Vernon expanded the idea of what a monument can be and who is worthy of being commemorated through a monument. While the representation of Keelan-Chaffins thus shows positive progress in the representation of disabled people, there are still problems with the lack of diversity in the representation of the disabled community that are perpetuated in Vernon’s artwork.

By analyzing Vernon’s artwork, I argued that artworks with durational disability aesthetics are important because they can show disabled people in public, normalize seeing human variety, give disabled people a voice, give meaning to their shared experiences, and create a way to strengthen the solidarity between people with disabilities. Vernon’s All the Way to Freedom is an example of durational disability aesthetics in which she combined individual and collective memories and experiences of people with disabilities to argue for the importance of accessible public spaces.

References

Bell, Chris. “Introducing White Disability Studies: A Modest Proposal.” The Disability Studies Reader, edited by Lennard J. Davis, 2nd ed., Routledge, 2006, pp. 275-282.

Deleire, Thomas.“The Unintended Consequences of the Americans with Disabilities Act”. Regulation, vol. 23, no. 1, 2000, pp. 21-24. Cato Institute, http://www.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/regulation/2000/4/deleire.pdf.

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature. 20th anniversary edition, Colombia University Press, 2017.

Garland-Thomson, Rosemarie. Staring: How We Look. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Ginsburg, Faye, and Rayna Rapp. “Making Accessible Futures: From the Capitol Crawl to #Cripthevote.” Cardozo Law Review, vol. 39, no. 2, 2017, pp. 699-718. HeinOnline, https://heinonline-org.ru.idm.oclc.org/HOL/P?h=hein.journals/cdozo39&i=729.

Goffman, Erving. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. 1963. Penguin Random House UK, 2022.

Kafer, Alison. Feminist, Queer, Crip. Indiana University Press, 2013.

Keelan-Chaffins, Jennifer. “All the Way to Freedom NOW!.” JKCLegacy, 29 september 2024, https://jkclegacy.com/blog/all-the-way-to-freedom-nownbsp. Accessed 12 December 2024.

Litowsky, Linda. “U.S. Capitol Crawl: Wheels of Justice Action.” Vimeo, posted by Stephanie K. Thomas, 3 April 2019, https://vimeo.com/328233990.

McRuer, Robert. “Compulsory Able-Bodiedness and Queer/Disabled Existence.” The Disability Studies Reader, edited by Lennard J. Davis, 4th ed., Routledge, 2013, pp. 369-378.

Melianto, Donny, and Ahmad Syamsudin. “The Role of Arts in Identity Formation and Collective Memory in The Digital Age.” Majority Science Journal, vol. 2, issue 4, 2024, pp. 73-80. Jurnal Hafasy, https://jurnalhafasy.com/index.php/msj/article/view/253.

Milden, Ian. “Examining the Opposition to the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990: “Nothing More than Bad Quality Hogwash”.” Journal of Political History, vol. 34, no. 4, 2022, pp. 505-528. Cambridge University Press, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0898030622000185.

Millett-Gallant, Ann. The Disabled Body in Contemporary Art. 2nd ed., Palgrave Macmillan, 2024.

Siebers, Tobin. Disability Aesthetics. University of Michigan Press, 2010.

Smith, S.E. “The Beauty of Spaces Created for and by Disabled People.” Disability Visibility: First-Person Stories from the Twenty-First Century, edited by Alice Wong, Vintage Books, 2020, pp. 271-275.

Vernon, Gina. “All the Way to Freedom NOW.” Gina Vernon Art, 30 September 2024, http://www.ginavernonart.com/blog. Accessed 12 December 2024.

Vernon, Gina. “Fighting for the Spirit of the ADA.” Gina Vernon Art, 6 December 2019, http://www.ginavernonart.com/blog/2019/11/21/sculpture-of-child-activist-celebrates-adas-30th-4k5xc. Accessed 12 December 2024.

Weissman, Terri. “Impossible Closure: Realism and Durational Aesthetics in Susan Meiselas’s Nicaragua.” Novel: A Forum on Fiction, vol. 49, no. 2, 2016, pp. 295-315. Duke University Press, https://doi.org/10.1215/00295132-3509051.

Marle Zwietering recently completed her MA in Art History at Radboud University and is currently doing the MA Literature and Society at Radboud University. She is interested in the representation of illness and disabilities in arts and culture and the intersection of disability studies with Feminist studies, Queer studies, and Postcolonial studies.